This blog post is the second in a series on autotracking, the new reactivity system in Ember.js. I also discuss the concept of reactivity in general, and how it manifests in JavaScript.

In the previous blog post, we discussed what it means for a system to be reactive. The definition I landed on for the purposes of this series was:

Reactivity: A declarative programming model that updates automatically based on changes to state.

I tweaked this slightly since last time so it reads better, but it’s effectively the same. In this post, I’ll discuss another aspect of reactivity in general: What makes a good reactive system?

Rather than trying to define this in a bubble, I’ll start by taking a look at the reactivity of a few other languages and frameworks. From these case studies, I’ll try to extract a few principles of good reactive design. This will, I think, both help to keep things grounded, and show a variety of different ways to accomplish the same fundamental goal. As I said in the first post of this series, there are many different ways to do reactivity, each with its own pros and cons.

I also want to say up front that I am not an expert in all of the technologies we’ll be taking a look at. My understanding of them is mostly based on research I’ve done during my work on autotracking, to better understand reactivity as a whole. So, I may get a few things wrong and miss details here and there! Please let me know if you see something that’s a little off (or completely backwards 😬).

HTML

In the last post, I used HTML as an example of a fully declarative language. Before we dive into some frameworks, I wanted to expand on that a little bit more, and also discuss the language’s built-in reactivity model. That’s right, HTML (along with CSS) actually is reactive on its own, without any JavaScript!

First off, what makes HTML declarative? And why is it so good at being a declarative language? Let’s consider a sample of HTML for a login page:

<form action="/my-handling-form-page" method="post">

<label>

Email:

<input type="email" />

</label>

<label>

Password:

<input type="password" />

</label>

<button type="submit">Log in</button>

</form>This sample describes the structure of a form to the browser. The browser then takes it, and renders the fully functional form directly to the user. No extra setup steps are necessary - we don’t need to tell the browser what order to append the elements in, or to add the handler for the button to submit the form, or any extra logic. We’re telling the browser what the login form should look like, not how to render it.

This is the core of declarative programming: we describe what output we want, not how we want it made. HTML is good at being declarative specifically because it is very restricted - we actually can’t add any extra steps to rendering without adding a different language (JavaScript). But if that’s the case, how can HTML be reactive? Reactivity requires state, and changes to state, so how can HTML have that?

The answer is through interactive HTML elements, such as input and select. The browser automatically wires these up to be interactive and update their own state by changing the values of their attributes. We can use this ability to create many different types of components, like say, a dropdown menu.

<style>

input[type='checkbox'] + ul {

display: none;

}

input[type='checkbox']:checked + ul {

display: inherit;

}

</style>

<nav>

<ul>

<li>

<label for="dropdown">Dropdown</label>

<input id="dropdown" type="checkbox" />

<ul>

<li>Item 1</li>

<li>Item 2</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</nav>My favorite example of these features taken to the extreme is Estelle Weyl’s excellent Do You Know CSS presentation. See the ./index.html example for a pure HTML/CSS slideshow, with some stunning examples of the platform’s native features.

In this model for reactivity, every user interaction maps directly onto a change in the HTML (e.g. the checked attribute being toggled on checkboxes). That newly modified HTML then renders, exactly as it would have if that had been the initial state. This is an important aspect of any declarative system, and the first principle of reactivity we’ll extract:

1. For a given state, no matter how you arrived at that state, the output of the system is always the same

Whether we arrived at a page with the checkbox already checked, or we updated it ourselves, the HTML will render the same either way in the browser. It will not look different after we’ve toggled the checkbox 10 times, and it will not look different if we started the page in a different state.

This model for reactivity is great in the small-to-medium use cases. For many applications, though, it becomes limiting at some point. This is when JS comes into play.

Push-Based Reactivity

One of the most fundamental types of reactivity is push-based reactivity. Push-based reactivity propagate changes in state when they occur, usually via events. This model will be familiar to anyone who has written much JavaScript, since events are pretty fundamental to the browser.

Events on their own are not particularly very declarative, though. They depend on each layer manually propagating the change, which means there are lots of small, imperative steps where things can go wrong. For instance, consider this custom <edit-word> web component:

customElements.define(

'edit-word',

class extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

const shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ mode: 'open' });

this.form = document.createElement('form');

this.input = document.createElement('input');

this.span = document.createElement('span');

shadowRoot.appendChild(this.form);

shadowRoot.appendChild(this.span);

this.isEditing = false;

this.input.value = this.textContent;

this.form.appendChild(this.input);

this.addEventListener('click', () => {

this.isEditing = true;

this.updateDisplay();

});

this.form.addEventListener('submit', (e) => {

this.isEditing = false;

this.updateDisplay();

e.preventDefault();

});

this.input.addEventListener('blur', () => {

this.isEditing = false;

this.updateDisplay();

});

this.updateDisplay();

}

updateDisplay() {

if (this.isEditing) {

this.span.style.display = 'none';

this.form.style.display = 'inline-block';

this.input.focus();

this.input.setSelectionRange(0, this.input.value.length);

} else {

this.span.style.display = 'inline-block';

this.form.style.display = 'none';

this.span.textContent = this.input.value;

this.input.style.width = this.span.clientWidth + 'px';

}

}

},

);This web component allows users to click on some text to edit it. When clicked, it toggles the isEditing state, and then runs the updateDisplay method to hide the span and show the editing form. When submitted or blurred, it toggles it back. And importantly, each event handler has to manually call updateDisplay to propagate that change.

Logically, the state of the UI elements is derived state and the isEditing variable is root state. But because events only give us the ability to run imperative commands, we have to manually sync them. This brings us to our second general principle for good reactivity:

2. Usage of state within the system results in reactive derived state

In an ideal reactive system, using the isEditing state would automatically lead to the system picking up updates as it changed. This can be done in many different ways, as we’ll see momentarily, but it’s core to ensuring that our reactivity is always updating all derived state.

Standard events don’t give us this property on their own, but there are push-based reactive systems that do.

Ember Classic

Ember Classic was heavily push-based in nature, under the hood. Observers and event listeners were the primitives that the system was built on, and they had the same issues as the browser’s built in eventing system. On the other hand, the binding system, which eventually became the dependency chain system, was more declarative.

We can see this system in action with the classic fullName example:

import { computed, set } from '@ember/object';

class Person {

firstName = 'Liz';

lastName = 'Hewell';

@computed('firstName', 'lastName')

get fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}

let liz = new Person();

console.log(liz.fullName);

('Liz Hewell');

set(liz, 'firstName', 'Elizabeth');

console.log(liz.fullName);

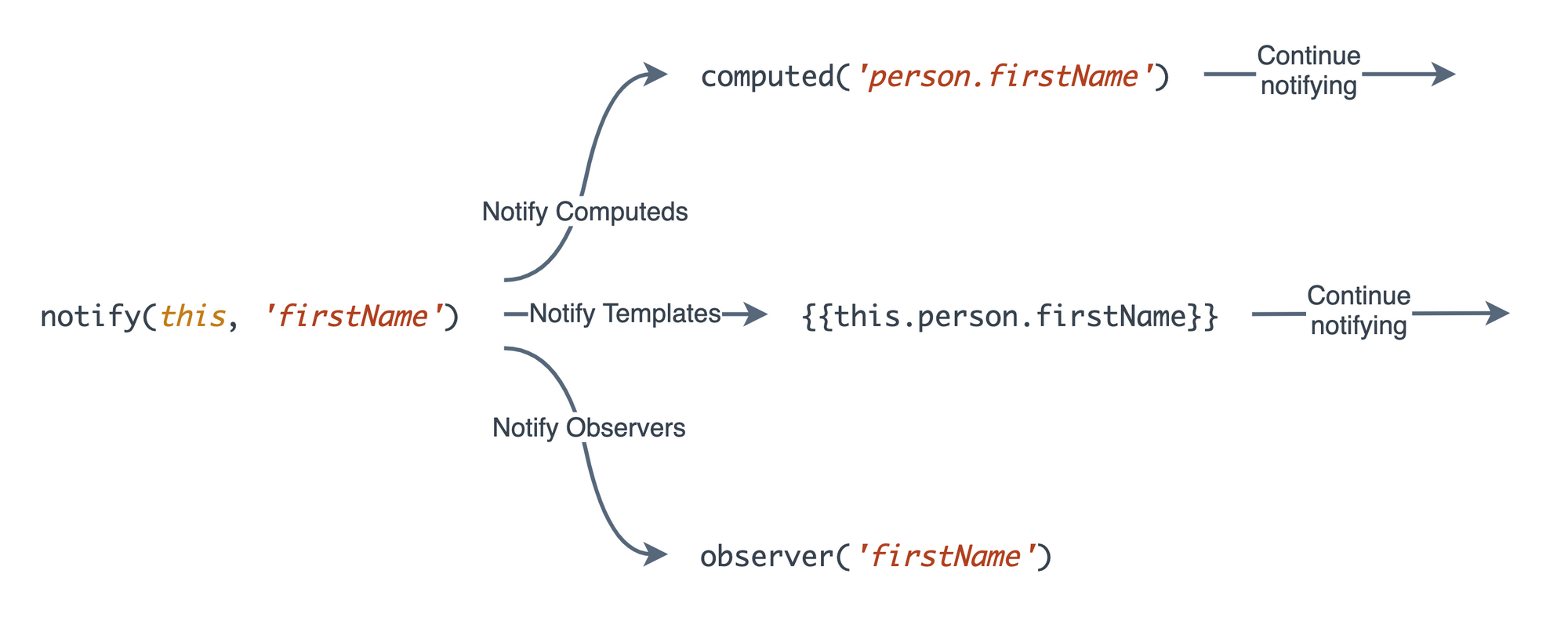

('Elizabeth Hewell');Under the hood in Classic Ember, this system worked via property notifications. Whenever we used a computed property, template, or observer for the first time, Ember would setup dependency chains through to all of its dependencies. Then, when we updated the property with set(), it would notify those dependencies.

Observers would run eagerly of course, but computed properties and templates would only update when used. This is what made them so much better than observers, in the end - they fulfilled the second principle of reactivity we just defined. Derived state (computeds and templates) became reactive when used, automatically.

This was the core of Ember’s reactivity for a very long time, and drove most of the ecosystem as observers fell out of common usage. It was not without its weaknesses though. In particular, it was a very object-oriented system. It essentially required defining objects and classes in order to setup dependency chains, pushing developers in this direction. Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is not a bad thing, but it can definitely be restrictive if it’s the only programming model available.

Also, while computed properties were better for performance than observers and event listeners on average, dependency chains and event notifications were still costly . Setting up the dependency system had to be done on startup, and every property change produced events that flowed throughout the entire system. While this was good, it could still have been better.

Observables, Streams, and Rx.js

Another take on the push-based model that makes things more declarative is the Observable model. It was popularized in JavaScript by RxJS, and is used by Angular as the foundation for its reactivity.

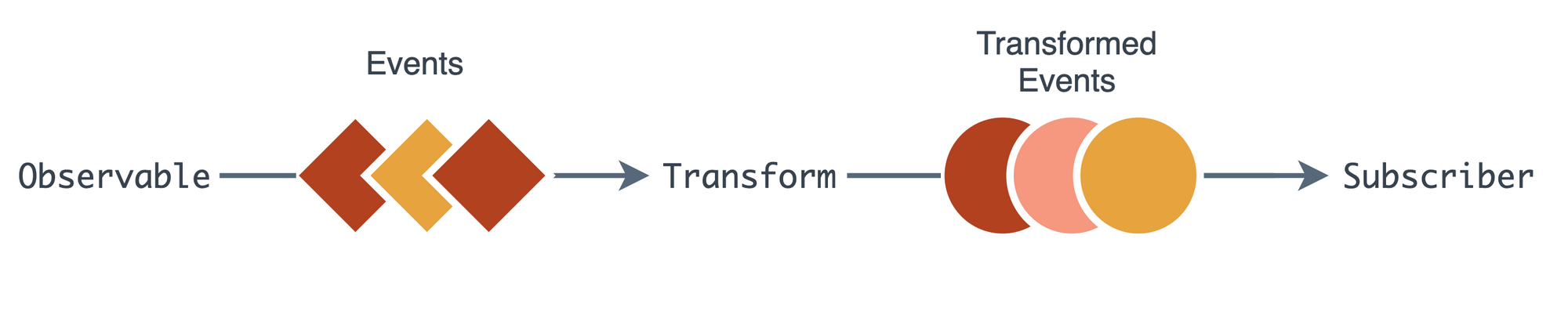

This model organizes events into streams, which are kind of like a lazy-array of events. Every time you push an event into one end of the stream, it will get passed along through various transformations until it reaches subscribers at the other end.

// Plain JS

let count = 0;

document.addEventListener('click', () => console.log(`Clicked ${++count} times`));// With Streams

import { fromEvent } from 'rxjs';

import { scan } from 'rxjs/operators';

fromEvent(document, 'click')

.pipe(scan((count) => count + 1, 0))

.subscribe((count) => console.log(`Clicked ${count} times`));This may seem similar to Ember’s observers on the surface, but they have a key difference - they are passed the values that they are observing directly, and return new values based on them. This means that they fulfill the second principle of good reactivity, because derived state is necessarily reactive.

The downside with streams is that they are by default always eager. Whenever an event is fired on one end, it immediately triggers all of the transformations that are observing that stream. By default, we do a lot of work for every single state change.

There are techniques to lower this cost, such as debouncing, but they require the user to actively be thinking about the flow of state. And this brings us to our third principle:

3. The system minimizes excess work by default

If we update two values in response to a single event, we shouldn’t rerender twice. If we update a dependency of a computed property, but never actually use that property, we shouldn’t rerun its code eagerly. In general, if we can avoid work, we should, and good reactivity should be designed to help us do this.

Push-based reactivity, unfortunately, can only take us so far in this regard. Even if we use it to model lazy systems, like Ember Classic’s computed properties, we still end up doing a lot of work for each and every change. This is because, at its core, push-based systems are about propagating changes when the change occurs.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are reactive systems that propagate changes when the system updates. This is pull-based reactivity.

Pull-Based Reactivity

I find the easiest way to explain pull-based reactivity is with a thought experiment. Let’s say we had an incredibly fast computer, one that could render our application almost instantaneously. Instead of trying to keep everything in sync manually, we could rerender the whole app every time something changed and start fresh. We wouldn’t have to worry about propagating changes through the app when they occured, because those changes would be picked up as we rerendered everything.

This is, with some hand-waving, how pull-based models work. And of course, the downside here is performance. We don’t have infinitely powerful computers, and we can’t rerender entire applications for every change on laptops and smart phones.

To get around this, every pull-based reactivity model has some tricks to lower that update cost. For instance, the “Virtual DOM”.

React and Virtual DOM

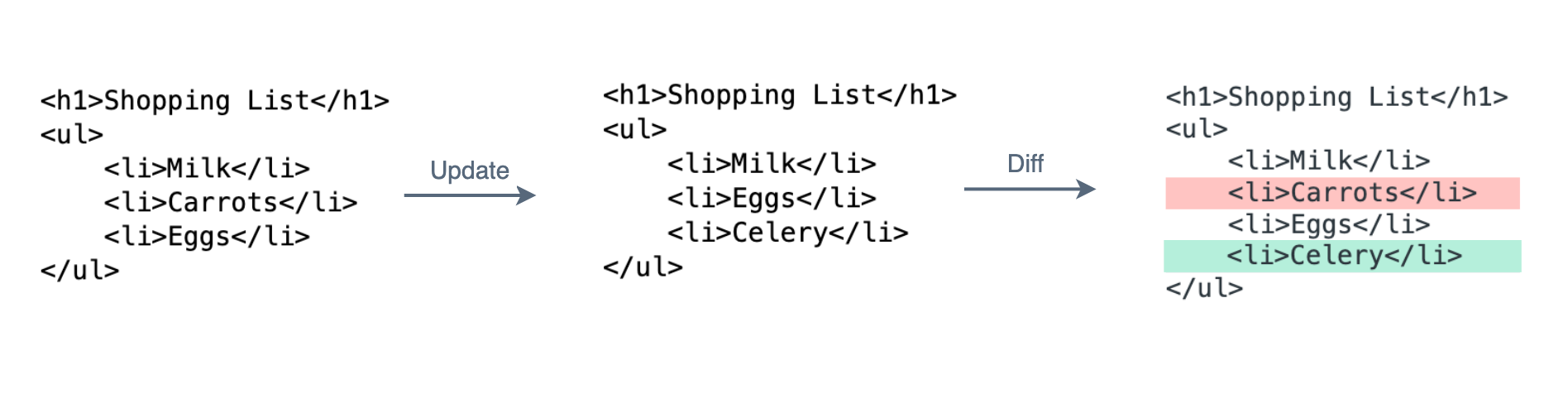

The Virtual DOM is probably one of the most famous features of React.js, and was one of the original keys to their success. The concept takes advantage of the fact that adding HTML to the browser is the most expensive part. Instead of doing this directly, the app creates a model that represents the HTML, and React translates the parts that changed into actual HTML.

On initial render, this ends up being all the HTML in the app. But on rerenders, only the parts that have changed are updated. This minimizes one of the most expensive portions of a frontend application.

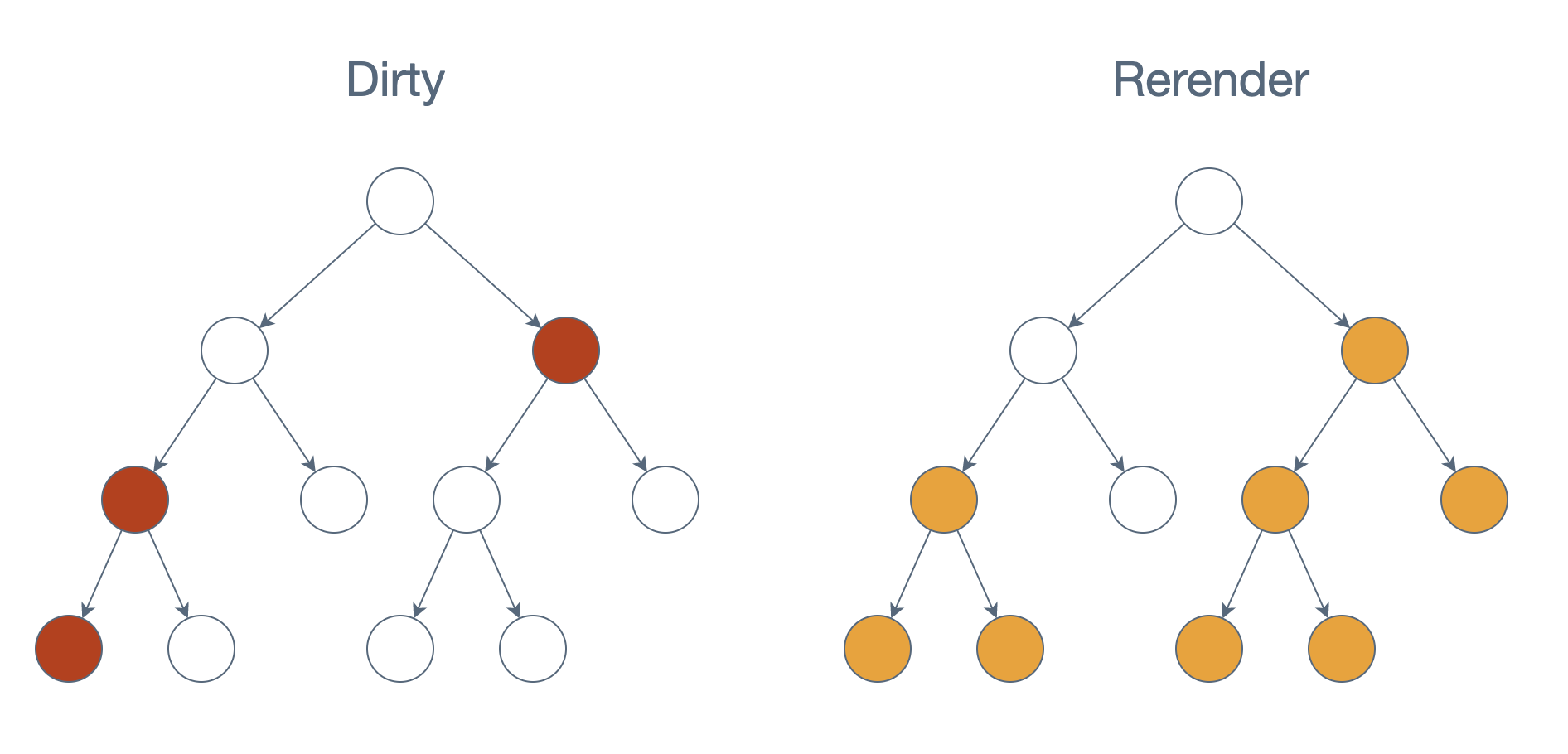

The second way that React’s reactivity model optimizes is by only rerunning the part that something has definitely changed in. This is partially what the setState API (and the setter from the useState hook) are about.

class Toggle extends React.Component {

state = { isToggleOn: true };

handleClick = () => {

this.setState((state) => ({

isToggleOn: !state.isToggleOn,

}));

};

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick}>{this.state.isToggleOn ? 'ON' : 'OFF'}</button>;

}

}When a user changes state via one of these, only that component (and its subcomponents) are rerendered during the next pass.

One interesting choice here that was made to maintain consistency is that setState and useState do not update immediately when called. Instead, they wait for the next render to update, since logically the new state is new input to the app (and necessitates another rerender). This is counter-intuitive to many users at first before they learn React, but it actually brings us to our final principle of good reactivity:

4. The system prevents inconsistent derived state

React takes a strong stance here precisely because they can’t know if you’ve already used state somewhere else. Imagine if in a React component we could change the state midway through render:

class Example extends React.Component {

state = {

value: 123;

};

render() {

let part1 = <div>{this.state.value}</div>

this.setState({ value: 456 });

let part2 = <div>{this.state.value}</div>

return (

<div>

{part1}

{part2}

</div>

);

}

}If the state change were applied immediately, it would result in part1 of the component’s template seeing the state before the change, and part2 seeing it after. While sometimes this may be the behavior the user wanted, it oftentimes comes from deeper inconsistencies that lead to bugs. For instance, you could render a user’s email in one part of the app, only to update it and render a completely different email in another part. React is pre-emptively preventing that inconsistency from appearing, but at a higher mental cost to the developer.

Overall, React’s two-pronged approach to reactivity is fairly performant up to a certain point, but definitely has its limitations. This is why APIs like shouldComponentUpdate() and useMemo() exist, as they allow React users to manually optimize their applications even further.

These APIs work, but they also move the system overall toward a less declarative approach. If users are manually adding code to optimize their applications, there are plenty of opportunities for them to get it just slightly wrong.

Vue: A Hybrid Approach

Vue is also a virtual DOM based framework, but it has an extra trick up its sleeve. Vue includes a reactive data property on every component:

const vm = new Vue({

data: {

a: 1,

},

});This property is what Vue uses instead of setState or useState (at least for the current API), and it’s particularly special. Values on the data object are subscribed to, when accessed, and trigger events for those subscriptions when updated. Under the hood, this is done using observables.

For instance, in this component example:

const vm = new Vue({

el: '#example',

data: {

message: 'Hello',

},

computed: {

reversedMessage() {

return this.message.split('').reverse().join('');

},

},

});The reversedMessage property will automatically subscribe to the changes of message when it runs, and any future changes to the message property will update it.

This hybrid approach allows Vue to be more performant by default than React, since various calculations can automatically cache themselves. It also means that memoization on its own is more declarative, since users don’t have to add any manual steps to determine if they should update. But, it is still ultimately push-based under the hood, and so it has the extra cost associated with push-based reactivity.

Elm

The final reactivity model I want to discuss in this post isn’t actually a JavaScript-based model. To me, though, it’s conceptually the most similar to autotracking in a number of ways, particularly its simplicity.

Elm is a programming language that made a splash in the functional programming community in the last few years. It’s a language designed around reactivity, and built specifically for the browser (it compiles down to HTML + JS). It is also a pure functional language, in that it doesn’t allow any kind of imperative code at all.

As such, Elm follows the pure-functional reactivity model I discussed in my last post. All of the state in the application is fully externalized, and for every change, Elm reruns the application function to produce new output.

Because of this, Elm can take advantage of caching technique known as memoization. As the application function is running, it breaks the model down into smaller chunks for each sub-function, which are essentially components. If the arguments to that function/component have not changed, then it uses the last result instead.

// Basic memoization in JS

let lastArgs;

let lastResult;

function memoizedRender(...args) {

if (deepEqual(lastArgs, args)) {

// Args

return lastResult;

}

lastResult = render(...args);

lastArgs = args;

return lastResult;

}Because the function is “pure”, and the arguments passed to it are the same, there is no chance anything changed, so Elm can skip it entirely.

This is a massive win for performance. Unnecessary work is completely minimized, since the code to produce the new HTML isn’t even run, unlike React/Vue/other Virtual DOM based frameworks.

The catch is that in order to benefit from this, you have to learn a new language. And while there are many potential upsides to learning Elm, and it is a beautiful language, it’s not always practical to switch to something less well-known and widely used.

Likewise, attempting to bring Elm’s pure-functional approach to JavaScript usually has varying degrees of success. JavaScript is, for better or worse, a multi-paradigm language. The model of externalizing all state also has issues, from lots of overhead conceptually to issues with scale. Redux is a library built around this concept, but even leaders in that community don’t always recommend it for those reasons.

What we really want are the benefits of memoization, but with the ability to store our state within the function - on components, near where it is used. And we want to fulfill all the other principles we’ve discussed as well.

But that’s a topic for the next post!

Conclusion

So, in this post we looked at a number of different reactivity models, including:

- HTML/CSS

- Push-based reactivity

- Vanilla JavaScript

- Ember Classic

- Observables/Rx.js

- Pull-based reactivity

- React.js

- Vue.js

- Elm

We also extracted a few general principles for designing a good reactive system:

- For a given state, no matter how you arrived at that state, the output of the system is always the same

- Usage of state within the system results in reactive derived state

- The system minimizes excess work by default

- The system prevents inconsistent derived state

I don’t think this list is necessarily comprehensive, but it covers a lot of what makes reactive systems solid and usable. In the next post, we’ll dive into autotracking and find out how it accomplishes these goals.