If you haven’t heard, Signals are a new proposal for the JavaScript language, and they’ve just entered stage 1! As a co-champion for the proposal, I’m personally very excited about this feature and its potential. Reactivity has become one of the most important parts of writing modern JS, and a decent amount of my time these days is spent running plumbing for reactive state - setting up and managing subscriptions and state on render, updating them on changes, and tearing them all down when the component is gone.

Frameworks have filled this void for the most part over the years and made this process much, much easier. I still remember the initial examples we saw of React Hooks, how they tied all of this management up into a neat package that didn’t require me to think of all of these things anymore:

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = props.source.subscribe();

return () => {

// Clean up the subscription

subscription.unsubscribe();

};

});This, to me, was the main reason hooks were so exciting. Yes, there was the fact that everything looked more functional, and functional languages were all the rage back then. And yes, it was cool that you could compose these hooks to create your own, nested hooks, really creating the potential for a whole ecosystem.

But the valuable insight, the core thing that hooks really got right, was realizing that the app’s lifecycle does not end at the component.

Before hooks, if you wanted to add and remove a subscription like in the above example, it was easy enough right in the component itself. But as your code started getting more complex, you would find yourself having to drill those lifecycle events down into every related function and class, and add boilerplate to every component to hook them up. It was just like prop-drilling, except maybe a bit worse because you had coordinate multiple lifecycle events every time. With hooks, you could easily avoid all of this because the those events were co-located in one place.

Since then, hooks-like reactivity patterns have proliferated and are now a core part of many frameworks, including Solid, Vue, Svelte (especially Svelte 5 with runes), and many more. These frameworks all approach things a bit differently, but at a high level each of them have the following:

- Root state, the fundamental state of the app (e.g.

useStatein React,createSignalin Solid,$statein Svelte 5, etc) - Derived state, values derived from other state that are invalidated and rederived whenever their inputs an updated (e.g.

useMemoin React,createMemoin Solid,$derivedin Svelte 5, etc.) - Effects, lifecycle functions that take state and turn it into side-effects, like writing to the DOM or subbing/unsubbing from a data source (e.g.

useEffectin React,createEffectin Solid,$effectin Svelte 5, etc.)

These core primitives are the basis of modern reactive JavaScript UI frameworks, and they’re also the basis for the design of the Signals proposal.

Cool! So, where are Effects?

You may have noticed that effects in the Signals proposal seem a little different. There’s Signal.State which is root state, and Signal.Computed is derived state, and these work pretty similarly to the frameworks I mentioned above. But the closest thing we have to an “effect” is Signal.subtle.Watcher which, (1) why is it under this subtle namespace? And (2) why does it seem fairly hard to use?

Back when hooks were first released, I was a member of the Ember.js core team and working on the next version of our own reactivity model which, eventually, became a sort of proto-signals like model. I’ve since moved on and now spend most of my time working on Svelte apps (with a couple of React projects in tow), but I learned a lot from my time on the Ember team and on that project, and I’ve dug into the guts of many Signals-like implementations over the years, so I’m fairly familiar with how they work across frameworks, where they are similar, and how and why they are different.

The easier parts of the design were root state and derived state, and this makes sense to me because these are very similar across most implementations. Without effects, a system of signals is a functionally pure reactive graph. State is consumed by functions, the results are cached and then consumed by other functions, until you get your result at the “top”, the original computed value that you were trying to get.

Effects, however, are trickier. Every framework approaches effects a bit differently, because they start to bring in concerns like app lifecycle and rendering. And in addition, there was a general sense among the framework teams that effects were a very powerful tool, and that they were often times misused in ways that caused a lot of developer frustration. In particular, there is one antipattern that effects encourage that is very widespread.

And that is managing state.

State is the enemy, state is always the enemy…

Consider the following Solid.js component:

function Comp(props) {

const [loading, setLoading] = createSignal(true);

const [value, setValue] = createSignal(undefined);

createEffect(() => {

setLoading(true);

fetch(props.url).then((value) => {

setLoading(false);

setValue(value);

});

});

}Something along these lines is a fairly common pattern in signals-based frameworks. What we have here is:

- A

loadingstate signal - A

valuestate signal - An effect that manages both of them.

This seems pretty straightforward. The fetch here is the side-effect - we’re sending a request for data out into the world, and when it returns we will want to update our value state and rerender. In the meantime, we set the loading state to show a spinner or some other UI to the user so they know what’s going on. We memoize the effect as well so that it doesn’t rerun unless props.url changes.

Seems simple enough! And at first, this pattern works really well. Beginners can pick up on it pretty quickly and it’s all fairly intuitive. But, things that start simple very rarely stay that way.

Disjointed Implicit Reactivity

In time, what you’ll find with the above pattern is that there is drift. More code gets added to the the effect (turns out we need to capture error states as well, oh and maybe we want to preserve the last value?) and it becomes more and more difficult to trace the line from effect to state. Multiple effects are added to the component, and sometimes the effects end up sharing state and mutating each other’s state. Maybe you want to load from cache first, but also do a background refresh. Maybe you have multiple fetchs that can all trigger the loading UI.

function Comp(props) {

const [loading, setLoading] = createSignal(true);

const [value, setValue] = createSignal(undefined);

const [error, setError] = createSignal(undefined);

createEffect(() => {

setLoading(true);

fetch(props.url).then((value) => {

setLoading(false);

setValue(value);

});

});

// if there was an error, load the backup data instead

createEffect(() => {

if (error && props.backupUrl) {

setLoading(true);

fetch(props.backupUrl).then((value) => {

setLoading(false);

setValue(value);

});

}

});

}What’s happening here, effectively, is that we are creating implicit dependencies between imperative effect code and declarative state/computed code. Or, maybe put another way, we are doing a bunch of imperative stuff in our otherwise functionally pure code, and bringing all of the problems of imperative programming with it. I call this disjointed implicit reactivity (credits to @benlesh for coming up with that), which is to say it is reactive code that no longer has an obvious, intuitive, and declarative flow, where each dependency is easy to see and understand. Instead, you have to start hunting for these implicit dependencies all over your app, and they can happen anywhere.

This is why in many frameworks, effects can become so monstrously complicated and difficult to debug. It is a core cause of action-at-a-distance in many apps, and it has caused many a developer pain and sorrow. So, what can we do?

Isolate the State

We can’t get rid of imperative code altogether. I mean, we can if we want to invent a new language, sure. But this is JavaScript, we don’t really have an alternative yet (though WASM is getting better every year…) and regardless, the shear amount of existing code out there is going to prevent most apps and devs from just switching over any time soon.

And in JS, you have to write imperative code sometimes. Our fetch example, for instance, is probably the simplest way you could fetch data from a remote backend without using external libraries, and it has a few imperative statements in it. You might be thinking “that’s not too bad though!”, but as we’ve seen this complexity can grow significantly over time.

So, what’s the alternative?

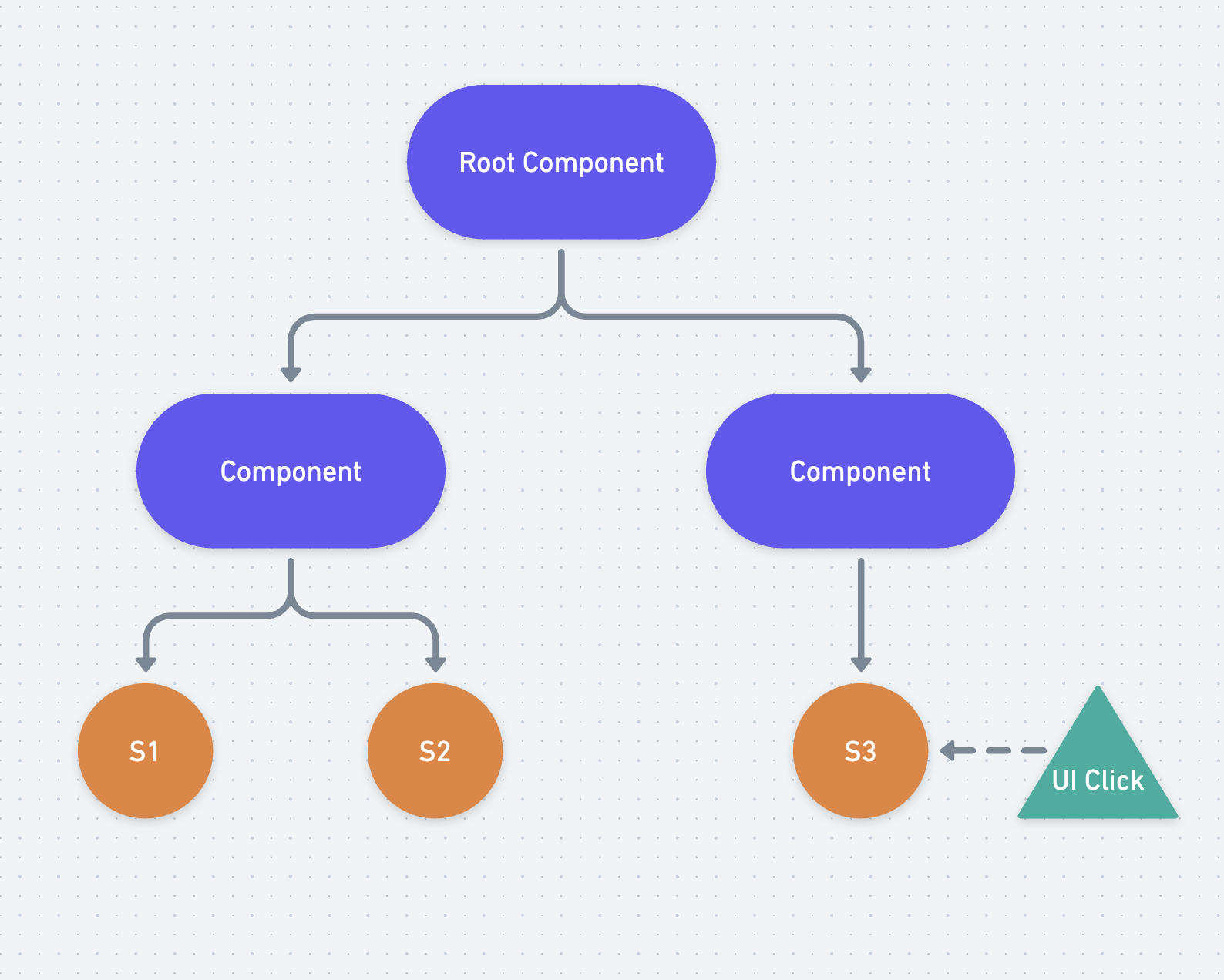

Let’s step back and look at a visualization of the problem. Here is a simple signals graph:

This graph doesn’t yet have any effects, it just has a few components and some state, and in one of the components, that state can be updated by a UI event. This is pretty straightforward to follow, we can see very easily where each piece of state enters the graph, what it’s updated by, and what depends on it. In general, most non-effect based updates will look like this - user events, interactions, browser APIs, maybe some top level communication with a service worker or something like that. If we didn’t ever need to load data, this would be pretty straightforward!

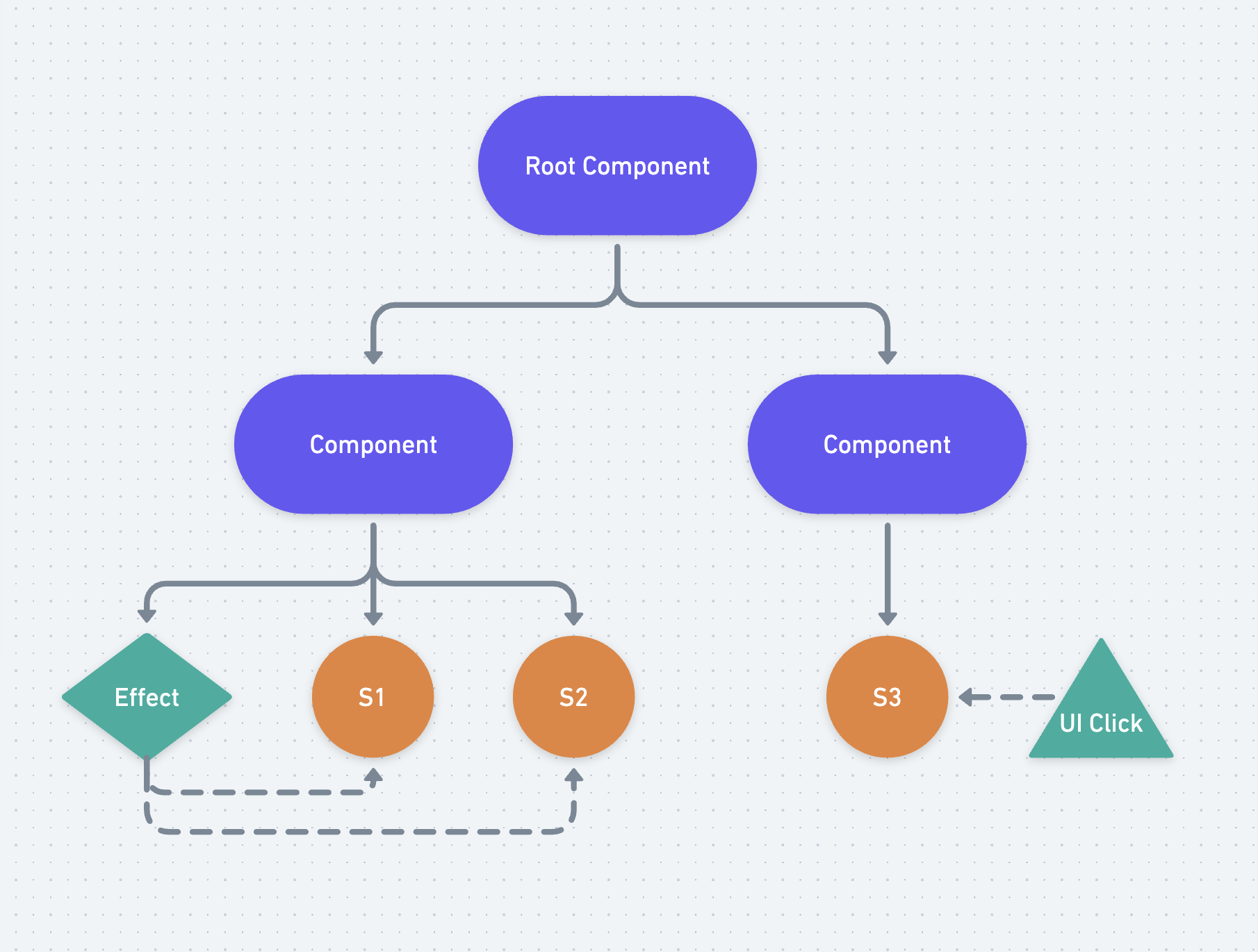

Now let’s add an effect:

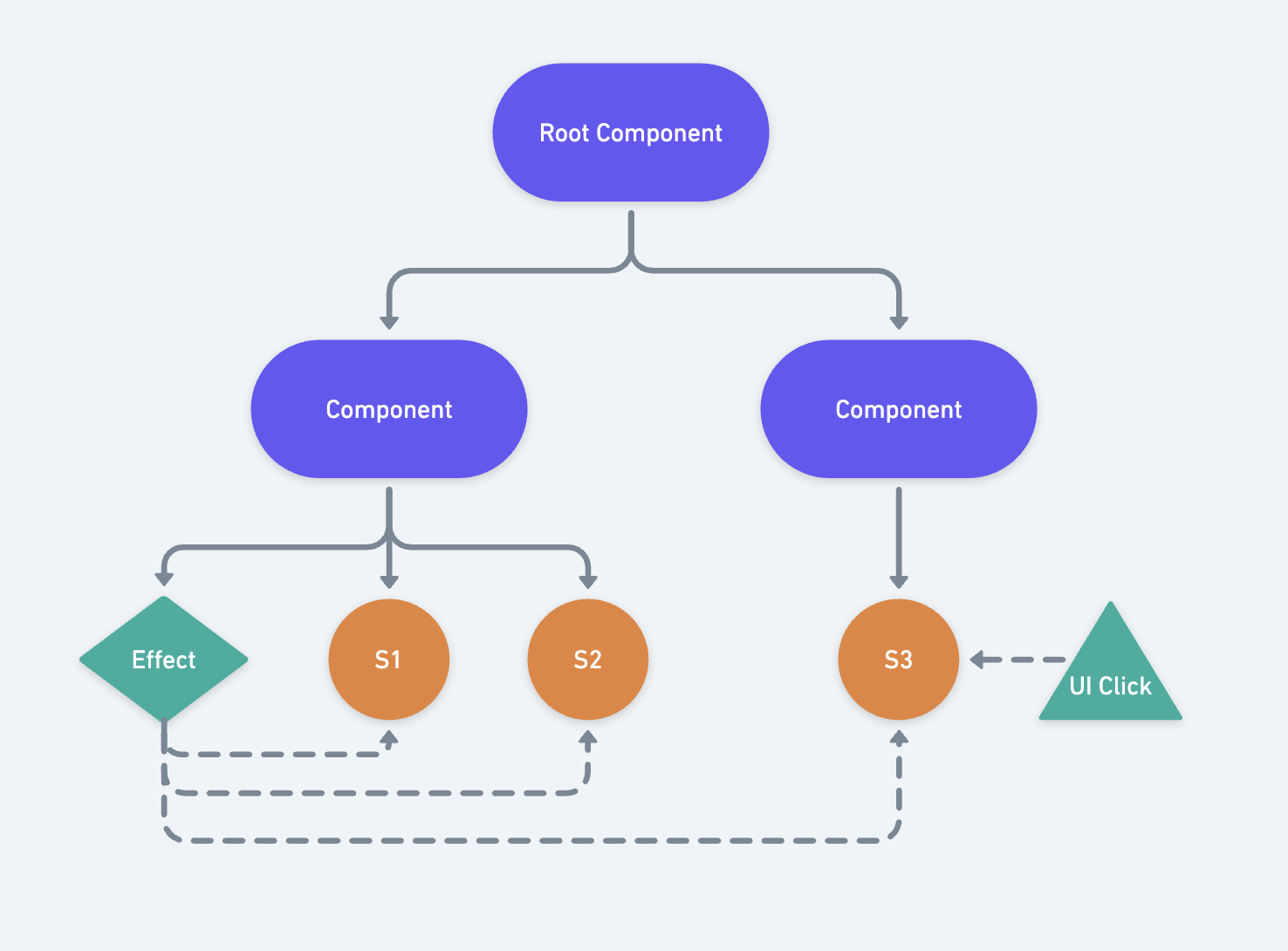

Ok, so the effect is the child of one of our components, and it updates the two pieces of state that are its siblings. We’re already starting to get a bit more complicated here, the interaction between the effect and its siblings is one step of indirection and requires the user to actually read the code. At first that’s easy, but what happens if we add 10 or 20 more states? Or, in the worst case, what about something like this?

Ok, now this looks like a strawman if I’ve ever seen one. Like, who would even build an app like this? It would require you to go out of your way for this to happen, to somehow get a hold of some piece of state in a completely separate component and start updating it. This is, of course, an oversimplified example.

But it’s more possible than you might think. I have seen such accidents in more complicated apps that have evolved slowly over time, where abstractions were made to handle loading state, and then remade a few times over, and then eventually you get something like this. Tech debt accrues, people leave and people join, and you end up with some rather gnarly looking code.

But what if it weren’t possible to do this? What if effects couldn’t write to just about any piece of state at all, and instead could only write to a limited scope, preventing these kinds of situations altogether?

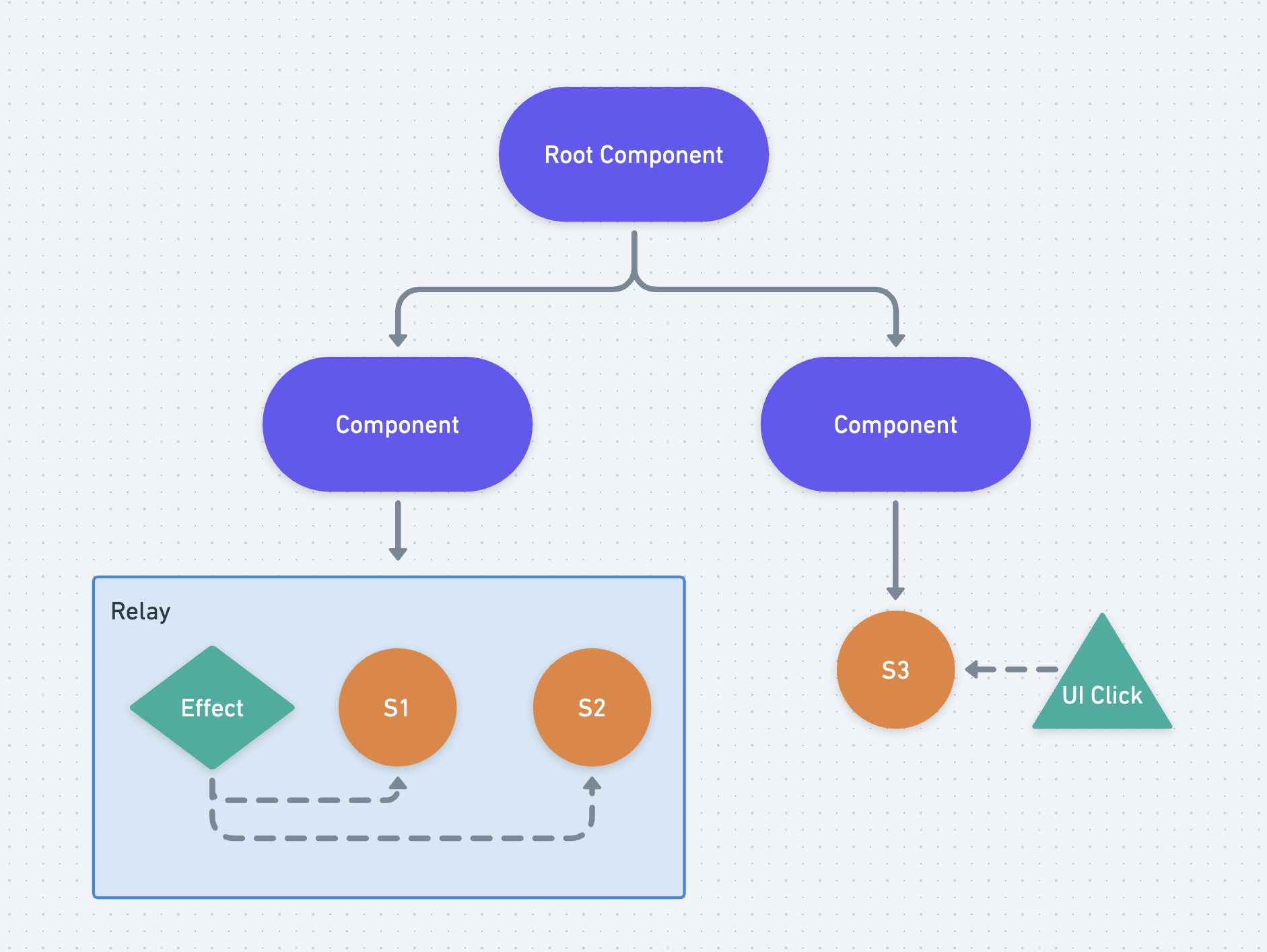

Here’s the same graph using a Relay, an abstraction that would provide a potential alternative to effects which would do just that:

The idea with Relays is that they are meant to bridge the results of an effect into the graph as state (thus the name relay, meaning “the act of passing along by stages”). Once the result is in the graph, it acts like any other piece of state, and every computed can treat it like a declarative dependency as-per-usual. And if you want to understand how that state is entering the graph, you just need to look one place - the definition of the Relay.

This is actually a fairly common pattern in the JavaScript ecosystem. The first time I remember seeing it was with SWR, which effectively creates a Relay for managing fetch requests, @modderme123 from the Solid team has written a blog post about it, and there’s even an issue opened by @dead-claudia, who came to a similar design independently, on the Signals repository at the moment. All this to say, this is already a fairly well established pattern, and it could even be considered a best practice at this point.

API????

Ok but what would it actually look like? Here’s my current thoughts with the existing Signals API:

declare class Relay<T> extends Signal<T> {

constructor(

initialValue: T,

<T>(set: (value: T) => void, get: () => T) => undefined | {

update?(): void;

destroy?(): void;

}

);

}This API is inspired by Svelte Actions, and splits out the lifecycle of side-effects into three parts:

- Initialization

- Update (optional)

- Destruction (optional)

In the lifecycle of a Relay, the function passed to the constructor is called to initialize the effect, state dependencies are tracked during initialization, and optionally users can return an object containing update and/or destroy. If the initial dependencies are invalidated, the update function is called to modify the effect that was created - the initialization function as a whole is NOT called again while the relay is still active. Finally, destroy is called when the relay is no longer in use in order to teardown the effect. If the relay is used again later, then initialization is called again and the whole lifecycle is restarted.

This API is a bit different than useEffect or createEffect style APIs which teardown the effect and recreate it on every change. The reasoning I have for this is that while tearing down and recreating is often a simpler API for most users, there are a decent amount of cases where you want to do something a bit more optimal during updates (e.g. maybe you just want to update a subscription and not tear the whole thing down). In my own experience this ends up being something like 20-30% of relays, and given this API is meant to be a language primitive to build upon, the thought is that we should support these cases by default and allow wrappers to be added that can simplify them at a higher level.

Here’s what it might look like in use as a fetch wrapper:

export const fetchJson = (url: Signal<string>) => {

return new Signal.Relay(

{

isLoading: false,

value: undefined,

},

(set, get) => {

// Note: set comes first in the API because every relay will

// need to `set`, but not every relay will need to `get`

// Setup some local state for managing the fetch request

let controller: AbortController;

// `loadData` is a local function to deduplicate the code

// in init and update

const loadData = async () => {

controller?.abort();

// Update isLoading to true, but keep the rest of the state

set({ ...get(), isLoading: true });

controller = new AbortController();

const response = await fetch(url.get(), { signal: controller.signal });

const value = await response.json();

set({ ...get(), value, isLoading: false });

}

// Call `loadData`, make the initial fetch, and track dependencies

loadData();

return {

update() {

// When dependencies update, call `loadData` again to

// cancel the previous fetch and make a new one.

// Dependencies are tracked again and fed into the next

// update.

loadData();

},

destroy() {

// Cancel any existing fetch request on destruction

controller?.abort();

}

}

}

);

}Note: This example uses just one externally exposed signal, but you could return an object containing multiple signals, or with getters that are backed by signals, enabling more fine-grained reactive control.

This neatly wraps up all of the details of fetching data in one spot so that you don’t need to manage those yourself every time. It maintains the lifecycle management benefits of effects, without allowing effects to write to anything they happen to have access to, thus preventing the issues that come with that.

Stepping back, the point here is actually about isolation of state. Relays let you isolate state in a way such that adding a relay doesn’t impact the behaviour of other relays on the page, and similarly removing them doesn’t cause unexpected changes. The business logic of a relay is a black box - you don’t need to know the details of it in order to use it, and it can’t affect anything else that you’re using around it.

Ok, Relays seem cool, but then why do we need Watchers?

Relays on their own are a great abstraction for managing effects and state together. But the issue is that if you start a relay, you will likely need to stop it at some point in order to clean up its contents and release whatever resources it may be using. In the subscription example, for instance, you would want to end the subscription when the relay is no longer being used (and also resubscribe if the relay ever enters the graph again).

This is tricky with just our three main concepts because there’s no simple way to tell when a relay is no longer in use. Let’s look at some options:

A relay is no longer in use when it is no longer consumed by any other derived state: This definition works for a single layer - if a

Computedreruns and no longer uses the relay (maybe it creates a new relay instead, for instance), then we can tear it down. The issue here though is that it doesn’t work with nesting. What if we stop using the computed itself? We need to be able to disconnect the entire subgraph that the computed is watching, not just its immediate dependencies.A relay is no longer in use when all of its consumers have been freed (popped off the stack or garbage collected): This definition relies on memory management and garbage collection, which means (A) the exact timing of teardown is no longer controlled by the user and (B) we can run into leaks very easily if we accidentally hold onto a computed/relay, or if we have a high continuous load and GC cannot occur. This would be a non-starter for any app of sufficient complexity.

A relay is no longer in use when all of its consumers have been explicitly destroyed: We could add a

destroy()method to all signals that explicitly disconnects them and leaves lifecycle management up to the user. There are two major issues with this:Signals don’t necessarily get destroyed and never used again. It’s more like they are no longer in use for now, and at some point in the future they may be used again. Consider for instance a data manager like Apollo Client which has

watchQuery, an API that creates a persistent, live-updating query on the data in Apollo’s cache. If the UI stops using that data, we don’t want to evict it from the cache, because the user may navigate back to the page that requires it and then we would have to fetch the data again. We want to stop actively subscribing to it for the time being, but if we ever start again, we want to be able to pick up where we left off.The exact timing of when we stop (and restart) a relay depends on when it is used by other derived state. For instance, let’s say that you have the following:

function Comp(props) { const data = new ApolloWatchQueryRelay(props.query); const showData = new Signal.State(true); const preprocessedData = new Signal.Computed(() => { return showData.get() ? preprocessData(data.get().value) : undefined; }); }If

showDatatransitions tofalse, the expectation would be that any subscriptions setup by thedatarelay would be torn down. That seems simple enough, we could do that like so:function Comp(props) { const data = new ApolloWatchQueryRelay(props.query); const showData = new Signal.State(true); const preprocessedData = new Signal.Computed(() => { if (showData.get()) { preprocessData(data.get().value) : undefined; } else { data.unsubscribe(); } }); }But what happens if the component itself is removed? Do we need to rerun all of its computeds in order to teardown all subscriptions? And what if multiple computeds are using the relay? We would need to add this management code to each of them. This would be a minefield of management for users and it defeats much of the purpose of signals by forcing users to constantly think about data consumption again, and forcing them to manage all the minutiae of manually subscribing, unsubscribing, etc.

Stepping back, the core idea of relays is that:

- They are active when they are being used either directly or indirectly by the “core app” (e.g. the UI in frontend apps, or a persistent process such as an actor or thread in backend apps).

- They are inactive when they are no longer connected to the core app via the signal graph.

In this model, Watchers represent that “core app”. A watcher essentially tells a signal graph that a given node is in use by some external process, so it should remain active. This pushes the complexity of lifecycle management up a level, to the framework that is handling the details of rendering, scheduling, and managing applications. Signal authors can create complex graphs of signals, hand them off to the app, and it can decide when it is watching the graph and when it wants to stop watching the graph. All the user has to do is define what happens when we start watching the graph, and what happens when we stop.

This is why the Watcher API feels like it isn’t really great for Effects - it’s not meant for them. It’s about extracting data from the graph and pushing that data elsewhere (or, in the case of graphs that use side-effects to write the data out, managing the active state of those effects). This is also why it was placed under the subtle namespace, the idea being that it would hint to developers that they should probably avoid using Watchers unless they are making a framework or other persistent process that needs to watch a signal graph.

Conclusion

So, to sum up this post:

- Signal graphs, in most implementations, consist of Root State, Derived State, and Effects

- Sometimes, Effects are used to update root state with the results of async processes

- A common anti-pattern is to manage multiple pieces of root state with a singfle effect, or to use multiple effects to manage a single shared piece of root state, creating difficult to debug ownership and timing issues. We can label this anti-pattern as “disjointed implicit reactivity”.

- Relays isolate and co-locate these effects with the root state they manage, preventing these issues by ensuring that there is one (and only one) place that the state can be managed and updated from.

My current opinion is that if we can gain consensus on the value of the Relay pattern, we can ship a version of Signals that provides better defaults for most users and prevents a lot of painful and difficult to debug situations. If nothing else, I sincerely hope that Signals users end up implementing this pattern more often rather than reaching for Effects directly. It has definitely improved my life in code, and I hope it can make yours easier as well!

Addenda

Are these really a full replacement for Effects?

There are really two categories of Effects that users end up writing often:

- Effects that push out of the graph, e.g. they take some state within the graph, read it, and push it out into the DOM or into some other system.

- Effects that push out of the graph, and then write the results back in to the graph, e.g. setting a State signal.

Relays are explicitly meant to fully replace the second category, and in my opinion are a much better solution for them. For the first, we could continue to have Effects and make a strong distinction between the two, but my preference would be to just have a Relay that doesn’t use its state value, like a computed that side-effects and returns undefined. It’s ultimately one less API to add, and if it really feels wrong to some, it’s trivial to wrap a Relay with an API that looks more like a plain Effect. But that said, I don’t have a strong opinion here and would be happy if both were added to the proposal.

Can’t users just use a Watcher directly? Or side-effect in a computed? Or do [insert-bad-thing-here] anyways?

Yes. Users will always be able to work around the bounds in JavaScript, especially when it comes to async and reactivity (and especially the combination of the two). This is not at all a silver-bullet, users could still create implicit dependencies all over the place with Relays (and Effects, if we also add them).

The goal of Relays is not to prevent all possible anti-patterns all the time. It’s to spread a known good pattern as the default, so that when users end up reaching for a side-effect they start by reaching for a Relay and, hopefully, end up with a fairly self-contained piece of code.

When I look at JS code in the wild, I’d say it’s split 60-40 or even more toward using effects that manages state for any one-off side-effecting thing. Most of the time users are using SWR or TanStack Query or some other abstraction which is effectively the Relay pattern for basic things like fetch, but it’s not the case much of the rest of the time. Ideally, Relays would help to shift the balance the other direction, so that most of the time for something basic that is just reading in state from a side-effect, users end up using a Relay.

You’ve talked a lot about fetch, what are some of the other things you could use this for?

Lot’s of things!

- Websockets could be managed with a Relay that manages the connection and exposes the messages as a queue that updates, or as the latest message to come through

- Connections to web workers or service workers could use Relays to facilitate passing messages to the worker (by autotracking dependencies, reading them, and sending them out) and then reading back results

- Web APIs like

IndexedDBthat are async storage mechanisms could be wrapped in Relays - On backends, queries to databases could be wrapped in Relays

- Likewise, subscriptions to message buses or producer/consumer queues could be managed by relays

Basically any time you have some async action that needs to read state into the graph, you can use a Relay. It’s a really powerful primitive!

Why weren’t these included in the proposal in the first place?

As I mentioned above, we couldn’t really get consensus and wanted to get the first draft of the proposal out the door so we could start gathering community feedback. We did, however, get consensus to add all of the APIs you would need to create a Relay abstraction.

That is the purpose of the Signal.subtle.watched and Signal.subtle.unwatched APIs. Without them, you could do most of the things a Relay needs to do using a combination of Computed and State signals that side-effect on initialization and during updates. But you couldn’t cleanup a computed that was no longer in use, or restart a computed that was just added back into the graph. So, those two events were added as a compromise to enable experimentation.